I. Foundational Due Diligence: Legal Compliance and Ownership Verification

This foundational inspection phase is critical, as failure to confirm legitimate ownership or regulatory compliance can result in the total financial loss of the asset, regardless of its mechanical condition.

A. Theft and Ownership Verification Protocol

The acquisition of a stolen electric bicycle carries the immediate risk of legal entanglement, confiscation, and voided ownership rights. Verification protocols must be multi-layered to mitigate this exposure.

The primary tool for due diligence is the Serial Number Verification process. The frame serial number, which serves as the bike’s unique identifier, must be meticulously recorded and checked against public, non-profit databases dedicated to tracking stolen bicycles. Recommended verification sources include Bike Index, Project 529 Garage, and Bike Register. While a clean search result confirms the bicycle has not been reported stolen, it does not, in isolation, validate the seller’s ownership.

Buyers must demand clear Proof of Ownership Documentation. Legitimate sellers should be able to provide the original proof of purchase receipt, official registration documents, or a formal Bill of Sale. A Bill of Sale is critical and should list the seller’s information, the date of sale, the bike’s make and model, and the unique serial number, adding legitimacy to the transaction. The inability or reluctance of a seller to provide documentation should be viewed as a significant warning sign.

A factor unique to e-bikes is the security of the battery system. The owner must provide all original battery keys and, if applicable, the keycard or code required for key replacement. Losing these keys creates a high-probability future financial cost and operational risk. A missing key means the buyer may be unable to unlock the battery compartment, replace the lock mechanism, or swap out the battery when it inevitably fails, potentially rendering the entire machine useless once the current battery reaches the end of its life. This inability to perform future maintenance or replacement of a key component must severely devalue the transaction.

Finally, the integrity of the serial number itself must be confirmed. In cases of theft recovery, serial numbers have been found to be missing or deliberately removed (e.g., stickers ripped off). If the serial number is obscured, damaged, or absent, the transaction should be terminated immediately, as proving ownership against a claim becomes virtually impossible, even when the buyer can describe detailed aftermarket parts.

B. E-Bike Classification and Compliance (The 750W Nominal Rule)

E-bike legality in the United States is governed primarily at the state level, with 36 states adopting a common three-tiered classification system based on maximum speed and motor assistance type. Buyers must confirm the specific classification of the used e-bike and its compliance within local jurisdictions.

The standard three classes are defined as follows 6:

- Class 1: Electric bikes with pedal assist only (PAS); motor assistance cuts off at 20 mph.

- Class 2: Electric bikes with PAS and a throttle; motor assistance cuts off at 20 mph.

- Class 3: Electric bikes with PAS only; motor assistance cuts off at 28 mph.

The critical motor power threshold for these classifications is a maximum of 750 Watts 6. This 750W limit typically refers to the nominal (continuous) wattage, which is the power the motor can sustain without overheating during prolonged operation. This nominal wattage is usually the number regulators use to classify the vehicle legally.

The distinction between nominal and peak power is crucial for the buyer. While the peak wattage can be much higher-often 1000W, 1200W, or more, representing a temporary burst for acceleration or climbing steep hills-legal limits focus on the lower, continuous nominal figure. Some manufacturers or sellers may exploit this regulatory focus by labeling a high-powered bike as “750W nominal” even if it runs significantly higher constant power through the controller. This practice poses dual risks: first, it risks premature motor failure due to overheating, as the motor is running beyond its designed continuous capacity; and second, it strains mechanical components (such as brakes and frame) that were designed only for a 750W nominal output system, creating an unreliable component package under a legally compliant sticker. Buyers must confirm the nominal wattage is compliant and should ask for the peak wattage to gauge real-world performance.

Devices that exceed the 750W nominal limit, provide throttle assistance above 20 mph, or lack pedals fall into a “Classless” category 6. These vehicles are often not considered low-speed electric bicycles and, depending on state law, may be regulated as mopeds or motorcycles. This misclassification can mandate licensure, registration, and insurance requirements for the operator, fundamentally altering the nature and cost of ownership.

Recommended: Which Electric Bikes Have Regenerative Braking?

Table 1 provides a summary of the standard US classification system and its associated risks.

Table 1: E-Bike Legal Classification and Regulatory Risk (US Standard)

| Class | Motor Assistance | Max Speed Assist | Throttle Allowed? | Legal Risk (Non-Compliance) |

| Class 1 | Pedal Assist Only (PAS) | 20 mph | No | Low (Highest Trail Access) |

| Class 2 | PAS & Throttle | 20 mph | Yes | Low |

| Class 3 | Pedal Assist Only (PAS) | 28 mph | No | Low-Medium (Helmet rules often apply) 13 |

| Classless | >750W Nominal/High Speed Throttle | Varies | Varies | High (Risk of Moped/Motor Vehicle Classification) 6 |

C. Detecting Illegal Modifications and Derestriction

Speed modifications, often called “tuning” or “derestriction,” are common aftermarket practices designed to override the legal speed limitations of 20 or 28 mph. These modifications severely stress the bike’s components, void any residual warranty, and expose the rider to severe legal penalties.

Tuning kits, such as physical dongles or chips (e.g., SpeedBox, BadassBox), function by being physically installed inline with the speed sensor, motor, or display unit. They “trick” the motor controller by sending a false speed signal, making the motor believe the bike is traveling slower than its actual speed, thereby delaying or preventing the power assistance from cutting off at the required legal limit.

Physical inspection for tampering should focus on these indicators:

- Non-OEM Wiring: Inspect the wiring harness, particularly near the motor (if mid-drive) or controller, for non-standard, “plug-and-play” modules inserted inline with the speed sensor cable.

- Physical Access Signs: Look closely for fresh tool marks, scratches, or loose screws around the motor casing or crank arms, which often must be disassembled to access the internal wiring for chip installation.

- Older Systems: On some older or more basic controllers, a dedicated speed-limiting wire might be deliberately snipped or looped back into the controller-look for non-connecting wires or quick disconnects in the bundle.

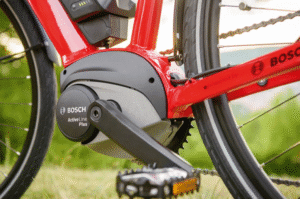

Sophisticated e-bike systems, such as Bosch, are capable of detecting manipulation, and tuning kits are notorious for triggering specific error codes (e.g., the Bosch “504 error”). If the seller reports recurring, specific error codes related to speed sensors or system communication, it is a significant indication of present or past tuning.

Recommended: 5 Fixes When Your E-Bike Battery Won’t Charge

The crucial consequence of illegal modification is the permanent voidance of the product warranty. As most e-bike warranties are non-transferable to a second owner 19, illegal tuning provides manufacturers with explicit and irrefutable justification to refuse any warranty claim should a part fail, even if unrelated to the tuning itself. This effectively shifts 100% of the financial risk of component failure onto the second-hand buyer.

II. The Electrical System Audit: Battery, Motor, and Controller

The electrical powertrain-specifically the battery-represents the single largest financial vulnerability in a used e-bike purchase. A detailed audit of this system is mandatory for accurate valuation and safety.

A. Assessing Battery Health and Remaining Capacity (The Primary Cost Driver)

The replacement cost of a lithium-ion battery is substantial, typically ranging from $400 to $900, but can exceed $1,200 for high-capacity or premium brand units. Given that e-bike batteries generally last only 2 to 5 years, this cost must be integrated into the bike’s overall valuation 20.

The most reliable indicator of remaining battery life is the Charge Cycle Count-the number of times the battery has been fully discharged and recharged 19.

- Professional Diagnostics: For proprietary mid-drive systems like Bosch or Specialized Turbo, the most accurate method is to obtain a diagnostic report from a certified dealer. This report provides the exact cycle count and an estimate of remaining capacity.

- Manual Estimation: If dealer diagnostics are unavailable (common for non-proprietary systems), the buyer must rely on the seller’s verifiable data and a rough calculation. The approximate number of charge cycles can be estimated by dividing the bike’s total mileage by the estimated range per charge 19. For example, a bike with 3,000 miles and a 30-mile range per charge has approximately 100 cycles 19. A quality battery is often guaranteed to retain at least 60% capacity remaining after 500 charge cycles 19. If the estimated cycles exceed 500, the capacity should be considered significantly diminished, and this should be factored into the price negotiation.

Beyond performance metrics, the battery’s physical condition and authenticity are critical safety checks. The casing must be inspected for cracks, dents, corrosion, or signs of water exposure, as physical damage compromises safety and indicates poor maintenance 23. Battery terminals must also be checked for corrosion and cleaned to ensure tight electrical connections.

Crucially, the battery and charger must be verified for safety through UL Certification (Underwriters Laboratories). The UL Mark indicates compliance with rigorous safety standards and guards against the use of cheap, unverified counterfeit batteries that pose a severe fire risk. The buyer should look for the official UL Mark on the battery case and cross-reference the serial information against the public UL Product iQ database. Additionally, check for original manufacturer holograms, serial number matching, and tamper-proof seals, as counterfeits often lack these security features.

The analysis of battery health leads directly to a necessary adjustment in the bike’s valuation. Since the warranty is typically non-transferable 19, and battery failure is inevitable, the buyer must proactively perform a rigorous financial risk projection. If the battery health is questionable (e.g., high cycle count, no verification, non-UL certified), the full replacement cost ($400-$1,200+) should be subtracted from the bike’s Fair Market Value to arrive at the true Adjusted Used Value.

Recommended: PAS Sensor Troubleshooting: Expert E-Bike Pedal Assist Repairs

Table 2: Battery Health Assessment and Financial Risk Matrix

| Condition Indicator | Inspection Method | Interpretation | Financial Risk Level |

| Charge Cycle Count | Dealer Diagnostic/Calculation (Mileage/Range) 19 | < 100 cycles = Low Wear; > 500 cycles = High Wear (Capacity likely <60%) 19 | Low to High |

| Battery Casing Integrity | Visual Check | Cracks, corrosion, or dents indicate potential internal damage 23 | High |

| Replacement Cost | Check OEM/Aftermarket pricing 20 | $400 – $1,200+ must be factored into FMV 21 | High |

| Authenticity | UL Database Search, Holograms/Serial Match 25 | Absence suggests counterfeit/unverified safety | Medium to Extreme (Fire Risk) |

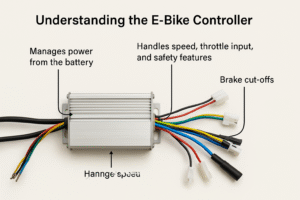

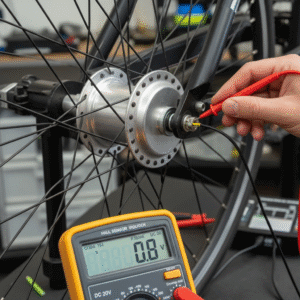

B. Motor and Controller Integrity Check

The motor and controller are responsible for power management and are susceptible to failure from overheating or environmental damage, particularly water exposure.

During the test ride, the buyer must assess motor functionality and noise. A high-quality motor, especially a direct-drive unit, should operate smoothly and silently when accelerating from a dead stop. Unusual noises, such as rattling, buzzing, clicking, or stuttering, are strong indicators of internal component issues, bearing wear, or physical damage.

The controller’s integrity must be checked for signs of water damage, a leading cause of erratic behavior (such as intermittent power delivery or erratic acceleration) or complete failure. A visual check of the controller casing and wiring harness should identify physical damage (cracks, burns), corrosion, or frayed/exposed wires. Specific attention should be paid to the battery terminals and electrical connectors for dirt, oxidation, or corrosion. The presence of corrosion signals moisture ingress into the electrical system, which can cause intermittent connections or short circuits and often predicts a cascading internal component failure. For advanced buyers comfortable with electrical troubleshooting, voltage checks using a multimeter can offer further diagnostic data, although professional inspection is recommended for complex issues.

III. Technical Mechanical Inspection Protocol

The mechanical components of an e-bike bear greater stress due to the increased weight and speed delivered by the motor. Therefore, the mechanical inspection must exceed the rigor applied to a conventional bicycle.

A. Frame and Structural Integrity (The Backbone Check)

The frame is the structural backbone of the bike and must be checked meticulously for damage, paying special attention to areas under high stress, such as the bottom bracket (where the motor mounts) and the battery cradle.

The entire frame should be inspected for cracks, deep dents, or rust. Weld points, particularly near the head tube and the junctions where the main tubes meet, are common points of fatigue failure. The buyer must understand that even a tiny, hair-like crack detected in a stress zone compromises the safety and structural integrity of the frame and requires professional assessment before riding. Additionally, wheel alignment should be verified to ensure proper handling and stability.

For full-suspension e-mountain bikes (eMTBs), the rear shock absorber mounting screws must be secure, and the shock itself should be tested for proper function.

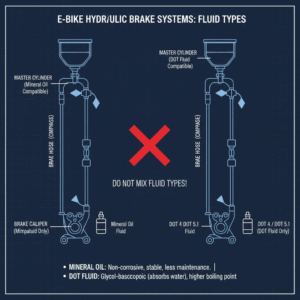

B. Braking System Functionality and Safety

Braking performance is non-negotiable for safety. The added mass and speed of e-bikes mandate fully functional and reliable braking systems.

- Brake Pad Wear and Function: Inspect the thickness of the brake pads; they should have a minimum of 1.5mm of friction material remaining. During the test ride, the brakes should be responsive and capable of stopping the bike quickly.

- Hydraulic Brake Leak Detection: If the bike uses hydraulic disc brakes, inspection for fluid leaks is essential, as this is a severe safety hazard. Inspect the calipers, brake lines, and the lever area (master cylinder) for any oily residue, wetness, or splattered fluid. After thoroughly cleaning the area, pumping the lever firmly and watching for seepage around the caliper seams, pistons, or bleed screws can confirm a leak.

- Lever Feel: When squeezed, the brake levers must feel firm and consistent. A soft or “spongy” feeling suggests the presence of air in the hydraulic line or dangerously low fluid, requiring immediate bleeding or repair.

- Rotor Condition: Check the brake rotors (discs) for warping, deep scoring, or cracks. Warped rotors cause a pulsing sensation when braking and compromise efficiency.

C. Drivetrain and Full Suspension Component Wear

The substantial torque delivered by an e-bike motor accelerates wear on the drivetrain components compared to conventional bicycles.

The chain and drivetrain must be checked for rust, stiffness, and wear. Inspect the chainrings (or dental discs) and cassette teeth for excessive wear. Worn teeth, which take on a “shark-finned” profile, cause the chain to slip under load, reducing efficiency and confirming the need for imminent, costly replacement.

For full-suspension eMTBs, the frame pivots and bearings are critical wear points. Pivot integrity can be assessed by grabbing the rear wheel at the top and pushing/pulling it sideways with force. Any perceptible lateral play or looseness indicates worn pivot bearings or loose bolts. Additionally, cycling the suspension through its travel should be smooth and free of “notching” or excessive friction, which are signs that bushings or bearings require service.

Because of the high forces involved (torque, speed, weight), seemingly minor mechanical issues in an e-bike-such as moderate drivetrain wear or slight brake sponginess-represent a much greater risk and imminent financial burden than they would on a traditional bicycle.

Recommended: Top Easy-Install 20-Inch Front Hub Motor Kits

IV. Financial Valuation and Risk Modeling

A specialized valuation approach is required for used e-bikes, as standard bicycle depreciation models fail to account for the unique financial risk posed by the electrical system’s components, particularly the non-transferable nature of the warranty and the inevitable battery replacement cost.

A. E-Bike Depreciation Benchmarks

E-bikes depreciate quickly due to the rapid advancement of electric motor technology, battery chemistry, and controller efficiency, rendering older models technologically obsolete faster than traditional bikes.

The established depreciation rate suggests a major loss of 40-50% in the first year of ownership, followed by a roughly 10% drop in value for each subsequent year. Consequently, a three-year-old model may be several technology generations behind, further accelerating its value loss. Buyers should target paying significantly less than 50% of the original list price for a used e-bike. The only mitigating factor is brand reputation; bikes from strong, high-quality brands like Specialized or Yeti tend to retain value better than generic models.

B. The Warranty Factor and Cost Integration

The non-transferability of warranties is a fundamental component of the used e-bike financial risk model. Most manufacturer warranties, including comprehensive service plans, do not transfer to the second owner 19. This means the buyer assumes 100% of the risk and cost for all future component failures, a risk manufacturers are known to leverage via expensive replacement parts to push new bike sales.

To accurately determine the purchase price ceiling, the buyer must perform a rigorous financial projection based on inspection findings. This calculation determines the Adjusted Used Value (AUV):

$$\text{AUV} = \text{FMV} – (\text{Estimated Battery Replacement Cost}) – (\text{Cost of Identified Repairs})$$

If the battery health audit indicates significant wear (e.g., cycle count over 500 19), the full replacement cost of a new battery-ranging from $400 to over $1,200-must be automatically integrated into the financial model as a necessary, sunk future cost, regardless of the bike’s current performance. This proactive financial deduction is essential to counteract the high price of manufacturer-specific replacement parts and the full assumption of risk due to the voided warranty.

V. The Test Ride and Transaction Security

The final stages of the process involve the comprehensive test ride to verify functionality under load and adherence to secure transaction practices to mitigate fraud risk.

A. The Comprehensive Test Ride Checklist

The test ride must specifically challenge the electrical and safety systems, confirming both performance and legal compliance.

- Motor and Power Delivery Test: The rider should cycle through all pedal assist levels (PAS modes) to confirm that power engagement is smooth and the output is consistent across all settings. If the bike is Class 2, the throttle must be tested for smooth, non-erratic speed control; intermittent or erratic behavior can indicate controller water damage. Listen intently for unusual motor noises, such as rattling or buzzing, especially during initial acceleration.

- Speed Cut-off Compliance: This is a crucial legal check. The rider must verify that the power assistance reliably cuts off at the specified legal maximum speed (20 mph for Class 1 and 2; 28 mph for Class 3) 6. If the motor continues to assist well past the legal limit without significantly increased rider effort, the bike is likely illegally modified (tuned).

- Braking Performance Under Load: Test both front and rear brakes dynamically, both at speed and on a slight incline. The brakes must stop the bike quickly and smoothly. Reconfirm that the levers feel firm and responsive, with no sponginess or pulsing (which suggests rotor warping).

- Drivetrain and Electronics Check: Confirm that gear shifting operates smoothly without skipping. Verify that all integrated electronics, including the display unit, lights, and any safety accessories (e.g., horn), are fully functional.

B. Safe Transaction Practices and Scam Avoidance

Due to the high value of e-bikes, private sales are frequent targets for financial scams and theft.

For personal safety and security, the buyer should insist on meeting in a public location, preferably a police station’s designated “online sale transaction zone,” which is typically under surveillance. If the seller objects to meeting in a secure, public area, this should be viewed as a red flag. When conducting a test ride on an expensive bike, the seller may request the buyer to leave significant collateral (e.g., wallet, car keys) to mitigate the risk of bike theft during the ride.

For financial security, the only secure payment method in private sales is cash-in-hand. The buyer must never accept or suggest suspicious payment methods, including wire transfers, money orders, cryptocurrency, Zelle, or PayPal Friends & Family, as these are frequently used in fraud schemes. A common financial scam involves the seller offering to “overpay” and then requesting the buyer to “refund the difference,” a tactic that guarantees losses for the buyer when the original payment is revealed as fraudulent. Finally, pricing that appears “too good to be true” (e.g., a high-end bike listed for less than $100) is an immediate indicator of a phishing or fraud attempt.

VI. Conclusions and Recommendations

The expert analysis confirms that buying a used electric bicycle involves mitigating complex technical, legal, and financial risks that are significantly greater than those associated with conventional bicycles. The valuation of the used e-bike is dominated by the health and replacement cost of the lithium-ion battery and the non-transferability of the manufacturer’s warranty.

Recommendations for Prospective Buyers

- Prioritize Ownership and Legal Status: The transaction must halt if proof of ownership (receipts/Bill of Sale) or all original battery keys are not provided. The serial number must be verified against stolen registries.

- Mandatory Battery and System Audit: The cycle count is the single most important technical metric. Buyers must calculate or obtain the cycle count and verify that the battery and charger bear the official UL Mark and match the product database. If battery health is questionable (over 500 cycles or unverified), the buyer should automatically subtract the full $400 to $1,200+ replacement cost from the purchase price.

- Confirm Compliance and Detect Tampering: Confirm the e-bike’s nominal wattage is 750W or less for legal compliance and rigorously test the speed cut-off during the test ride (20 or 28 mph). Any signs of tuning modules, modified wiring, or chronic error codes invalidate the warranty and suggest mechanical overstress.

- Seek Professional Consultation: Given the complexity and high risk of failure in the electrical and structural systems, an investment of $50-$100 for a pre-purchase inspection by a professional mechanic is strongly recommended. This mitigates the potential assumption of thousands of dollars in hidden repair costs or pending component failure.